Moss is tough. Its ancestors emerged from the oceans almost half a billion years ago, and it thrives to this day in some of the most objectionable environments on the planet. Now it has been shown that moss spores can survive at least nine months of exposure to outer space. Not just in some cozy orbiting capsule pampered by shielding, but exposed to the hideous elements.

This is an extraordinary feat for a life form. “Most living organisms, including humans, cannot survive even briefly in the vacuum of space,” points out Tomomichi Fujita, coauthor in the study published Thursday in the Cell Press journal iScience with Chang-hyun Maeng and colleagues of Hokkaido University, which investigated the survival of moss in outer space. “However, the moss spores retained their vitality after nine months of direct exposure. This provides striking evidence that the life that has evolved on Earth possesses, at the cellular level, intrinsic mechanisms to endure the conditions of space.”

Does this mean we can’t move to Mars but moss could? Or that if we make like moss, maybe we could one day? No. But maybe it could help us continue to live here.

Extremophile bacteria and archaea flourish in extremes such as volcanic hotspots and toxic lakes and are thought to be relics of the earliest forms of life. Less well-known are mosses that arose later but also thrive in a vast range of conditions, from mountain peaks to baking deserts to the polar tundras. Now we know that spores of Physcomitrium patens moss survived space to such an extent that back home on Mother Earth, over 80 percent of them could reproduce.

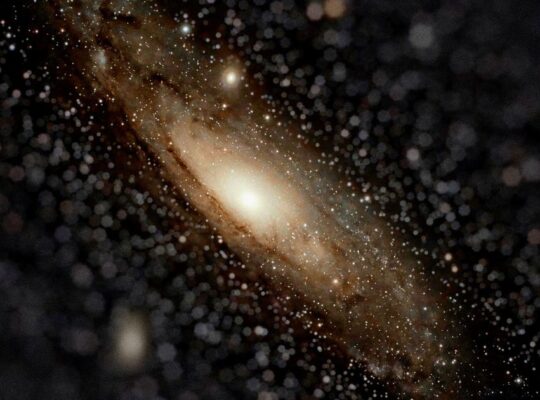

Why does that matter? “It has become increasingly important to explore new possibilities for the survival of life beyond our planet,” the authors explain.

That is true. We are rapidly creating ever-expanding swathes of uninhabitable land. The work seems to imply that the discovery of moss’ hardiness could lay the groundwork for terraforming alien worlds, culminating in extraterrestrial agriculture.

But that’s no solution. We are closer to peak metal (running out) than we are to warp drive. We can’t even terraform the Dust Bowl, let alone another planet – not that we can reach one anyway. Humanity is not going to move en masse or even en dozens to the Moon, let alone Mars. What does it matter if moss sporangia or the reproductive organs of any other primitive plant can survive on the International Space Station?

Fujita doesn’t disagree. But as he explains by email, “Studying the hardiness of moss spores helps us explore fundamental questions about biological limits, which could inform small but meaningful innovations in both space and terrestrial contexts. For example, uncovering mechanisms of stress tolerance in moss may help us develop more resilient plants for degraded environments on Earth.”

Could the miserable trajectory of humanity be changed, even a little bit, by the adventures of moss in space?

A very early plant

What is moss? It descended from algae and became one of the first plants to occupy the land. If we want to research the boundaries of botanical tolerance, moss that survived in so many conditions on Earth is a good candidate.

Out of all mosses, the team chose P. patens as a representative for the same reason other researchers choose to work with white mice and Drosophila fruit flies – they are very thoroughly researched. We know their genetics and norms.

Moss can reproduce asexually or sexually. Asexual reproduction is when a moss clump breaks up and each bit forms a new colony – like when you cut a worm in half and get two worms (but don’t do that, they don’t like it). Sexual reproduction involves moss egg and sperm that create a sporophyte, which produces spores. Each spore has the potential to turn into a moss plant that can be male, female or both.

Before their adventure, the spores were tested in a simulated space environment. They survived. Check. Then came liftoff aboard the Cygnus NG-17 in March 2022. The spores were still encased in their natural capsules but were placed into aluminum “space exposure utensils” that the astronauts attached to the outside of Japan’s “Kibo” module on the ISS.

Thus the spores were exposed to true outer space for 283 days all told. Some samples were shielded from ultraviolet radiation (“space dark”) while others were exposed to the sunlight, unshielded from the vacuum ultraviolet radiation, which poses a huge danger to astronauts and orbiting vegetation alike. They experienced extreme high and low temperatures, and vacuum conditions. The spores then rode back home on SpaceX CRS-16 in January 2023 and were chauffeured to the lab for testing. The team assumed they’d all be dead.

Not so! The spores had grimly hung on and 80-percent germinated, despite having been exposed to -196°C for over a week, and lived in 55°C for a month. The team posits that the sporangia capsule surrounding the spores may have helped shield the little things physically and chemically. “We were genuinely astonished by the extraordinary durability of these tiny plant cells,” Fujita says, as say we all.

This does augur well for the future of moss. Yay moss. Our future is another question.

Did the extreme stresses affect the spores? Were the ensuing plants normal, a little off-kilter, mutated, or demanding that the team take them to our leader? This is still being checked – they look fine, Fujita answers. Meanwhile, what the experiment achieved was to demonstrate the resilience of life.

If I am alive

But there is an anomaly. The spores were exposed to outer space, where nothing can survive. There are no resources – no air, no nutrients, no Netflix. Yet they survived for 9 months.

How? Surviving implies they were completely inert when dormant, that they had no metabolism at all; but then they would be dead and resurrection is not a thing.

Fujita answers that apparently, P. patens spores enter dormancy under arid conditions and do retain some drastically slowed state of metabolic activity. They approach the point of near-complete metabolic arrest, but do not cross it. “This dormancy likely enables them to remain viable for extended periods in harsh environments, both on Earth and – as our study suggests – even in space,” he sums up.

How? We don’t know. The experiment shows is that we do not understand dormancy, certainly not at the levels of gene expression, epigenetic modifications, protein function and enzymatic activity, he sums up.

If they had some metabolism, this implies that the moss spores probably couldn’t have survived much longer, though he notes they estimated the P. patens spores might theoretically survive up to around 15 years in space – not counting synergistic damage caused by prolonged exposure to multiple space stressors such as space radiation, vacuum, microgravity and extreme temperature fluctuations.

“I suspect that dormancy is not a single, uniform state; rather, it may vary depending on the type of cell, tissue or organism. This complexity is something that deserves much more scientific exploration,” he adds.

Sorry, no we cannot put people into hibernation or cryosleep – at best, we can achieve induced coma.

So what have we? One of Earth’s earliest plants proves to have extraordinary survival capability in its dormant form, which makes sense if we consider the enormous range of conditions it did and still does survive. Go you, moss. Maybe one day, this work can advance research leading to exploitation of extraterrestrial soils, or at least feeding astronauts on spaceships. More plausibly, maybe one day this work may help feed us right here.

Clarifying how moss might grow under harsh space conditions could also inform the development of more robust moss species suited for use on Earth, Fujita points out: “Mosses are pioneer plants that historically contributed to land ecosystem formation by aiding soil generation and moisture retention. If we can develop varieties that thrive in degraded environments, they may help slow or reverse terrestrial land degradation, increase vegetative cover and potentially expand arable land. In that sense, these small moss spores might play a quiet but powerful role in supporting future human sustainability – both in space and back here on Earth.

“This is not about escaping Earth – but about better understanding how to sustain life, adapt and regenerate ecosystems under growing environmental stress,” he says. “And if such findings one day contribute even a tiny piece toward the larger puzzle of planetary terraforming, I would be honored.”