Your life partner finishes a phone conversation with her mother and says it was “a bit heavy.” She doesn’t explain further, only shrugs her shoulders and adds that it was nothing special. You, however, hear between the lines that she was deeply hurt. You cancel whatever you had planned for that evening, listen again to the small details, offer a massage.

Later she says that there had indeed been an unpleasant moment with her mother, but not something that truly unsettled her. Even so, that small misunderstanding drew you closer: She felt that someone was taking her emotional world seriously, while for your part, you felt connected and valued within the relationship.

The ability to precisely identify the emotions of others constitutes the foundation of all social interaction. But this involves more than perceiving whether someone is angry, happy or frustrated – it also entails gauging the intensity of those emotional states.

This challenge appears incessantly in everyday life. Recognizing that your child is enjoying school or that a colleague at work is disappointed by a project delay is only the first step. An additional, essential skill lies in the ability to assess whether the child is truly happy or only fairly satisfied, whether the colleague is only somewhat disappointed or is thinking about resigning.

Estimating the intensity of what another person is feeling is what guides our responses and shapes the quality of our relationships.

Until now, researchers have focused on how accurately people can identify the type of emotion others express, largely neglecting the ability to gauge its intensity. A ride that an Israeli researcher once gave a colleague changed the whole picture, giving rise to a study that uncovered an important cognitive bias in this field.

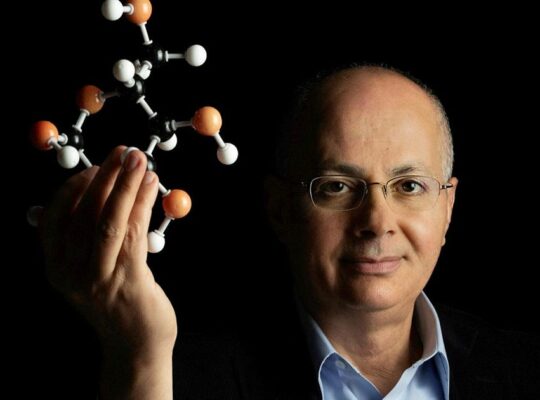

Anat Perry of the Psychology Department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem has been investigating empathy and how we understand others’ emotions for almost 20 years. “Over the years, we examined people’s empathetic precision in a great number of ways intended to simulate reality,” Prof. Perry tells Haaretz via Zoom from Boston, where she is on sabbatical.

In her experiments, Perry recorded people telling stories of life experiences, and then asked them to rate what they felt when telling their stories. She then played the recordings to others, and asked them to rate what they think the people telling the stories felt.

“We did this in all kinds of conditions – with video, audio, text,” the professor explains. “We even played the stories to people who hadn’t slept well at night, to see how that affects empathy. But all these studies examined what we call ’empathic accuracy’ – the degree of accuracy in assessing others’ emotions and what affects it.”

A few years ago, Prof. Noga Cohen, head of the Department of Special Education at the University of Haifa, gave a lecture in Perry’s lab. Afterward, Perry gave Cohen a lift from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv, and they started discussing their research. During their conversation, Cohen asked Perry whether she had ever examined the possibility that a regular pattern exists when people mistake the intensity of others’ emotions. Perry told her she hadn’t.

It wasn’t by chance that Cohen raised the question. “Seven years ago,” Cohen says, “when I was doing a postdoc at Columbia, I conducted research about how people help others. Participants in the experiment were asked to describe in texts what they saw as eight negative incidents and eight neutral incidents, and to rank the intensity of emotions such as anger, fear, sadness, happiness or pride in connection with each one.

“Afterward,” she continues, “we gave 50 other people the texts the participants wrote, and asked them to rank how those who experienced the events felt and to write letters of support. We were researching how people offer support, but I noticed that the readers always ranked the events more negatively than those who had actually experienced them.”

Cohen didn’t continue exploring her discovery but remembered it because it was counterintuitive. It seemed more reasonable to assume that people would perceive their own experiences as dire, while what happens to someone else would be perceived as less terrible – as “the troubles of others.” But the opposite proved to be the case.

Following the conversation they’d had during the ride, Perry, together with a PhD candidate, Shir Genzer, examined the data that had accumulated from Perry’s research over the years. “We suddenly discovered a strong, vivid truth,” Perry says with excitement (quite intense, in the author’s assessment). “Over and over again – in video, audio and text, even in live interaction, across different countries – we found that people slightly exaggerate when gauging others’ emotions as compared with the other individuals’ own assessments, and especially in negative emotions.”

This finding is unusual in the world of social science research, Perry says, noting that with human behavior, the results are rarely this clear-cut. “I love the fact that a phenomenon like this emerged from a chance conversation during a car ride,” she says.

The experiments conducted by Cohen and Perry involved subjects who assessed the emotions of strangers, so the researchers wanted to know if this bias exists when you know the other person well. To examine this issue, they turned to Prof. Eshkol Rafaeli of Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, who studies the phenomenon of empathic accuracy in couples. His database showed that partners also tend to exaggerate the intensity of each other’s negative feelings.

Perry: “People often think we perceive the world as it is, as though the eye is a camera that simply broadcasts what exists to the brain. But that’s not how our mind works. There’s a host of cognitive biases, some of them very basic, at a level where people perceive things that don’t exist.”

She describes the Kanizsa Triangle test, in which subjects are shown three circles with a segment missing, like three Pac-Men; most people report seeing a white triangle, even though there isn’t one. Another experiment involves showing footage of the same game to fans of opposing teams.

“They described what was happening on the field completely differently, because each focused on something different,” Perry notes. “There’s a gap between what is perceived and what actually exists. Similarly, where we found a new bias manifested in a range of contexts and cultures – meaning that it may have important value in our social world.”

The newly discovered bias was described by Genzer, Cohen and Perry and their colleagues in a paper published in Nature Communications in December 2025. Their findings were based on eight studies in three countries – Israel, the United Kingdom and the United States – involving almost 3,000 participants.

“The prevailing view is that the evolutionary source of empathy lies in the bond between parent and offspring,” Perry explains. “A mammal that was attentive and empathetic to the needs of its offspring increased their prospects of surviving, so that trait survived. The same can be said about the bias we found. Because it’s impossible to know exactly what an infant is feeling, it’s evolutionarily preferable for the parent to slightly exaggerate in this regard, especially when it comes to negative emotions.”

Over generations, those who were more likely to survive inherited this trait from their “exaggerating” parents. “Over time the trait spread to other people beyond the offspring, because it helps us avoid overlooking another person’s distress,” Perry says. “We are super-social beings, and this is a tool that helps us navigate the social world.”

The bias not only helps us help others; it can also be personally beneficial. For example, when early humans heard a cry of fear from someone in their group, those who thought the situation was somewhat more dramatic than it actually was had a better chance of surviving than those who attributed less urgency to it – or even those who identified the degree of fear accurately.

But what if the findings don’t show that people exaggerate the intensity of others’ negative emotions, but rather understate their own – perhaps because they’re accustomed to coping with their own difficulties?

Cohen responds with a folktale about a group of people, each carrying a sack filled with their troubles on their backs. One evening they gather, place their sacks in the center and decide that everyone may choose whichever sack they want. They examine the sacks, and in the end, each person takes back their own sack.

Cohen: “The present study shows that the troubles of others do indeed appear bigger than they are. But we don’t think that people minimize their assessment of their own troubles. Underestimation or overestimation of one’s own emotions is generally related to personality differences and depends on context, whereas here we found the same effect across a variety of studies. This suggests that the effect is probably driven by the perceivers, not the speakers.”

Exaggeration has adaptive value only when it is moderate. “If an infant grumbles a little and the mother responds quickly, that’s good,” Cohen says by way of example. “But if the mother responds in an extreme way, with a flood of emotions, that won’t help the baby.”

Empirical research on couples in romantic relationships showed that only moderate exaggeration is beneficial. Using “diary studies,” in which romantic partners fill out a daily questionnaire before sleep, researchers asked, among other variables, how participants felt throughout the day and how they believed their partner felt.

Couples who showed a moderate overestimation of negative emotions were more satisfied with their relationship than those who showed strong overestimation, those who underestimated, and even those who assessed emotions accurately. Here, too, the hypothesis is that perceiving a partner’s negative emotions as slightly stronger than they actually are cultivates closeness and encourages supportive behavior.

No similar findings among such couples emerged when it came to positive emotions. This did not surprise Prof. Rafaeli, because, he says, these are two systems of emotion which operate completely differently.

“The evolutionary logic regarding very negative emotions has been very clear since Darwin,” he says. “Precision in identifying the type of negative emotion, combined with slight exaggeration of its intensity, promotes an empathic response. Positive emotions, by contrast, don’t help us avoid mistakes or danger, but strengthen inner resources and social ties, so their assessment works differently.

“In that sense,” he continues, “I think [poet] Yehuda Amichai was mistaken when he wrote about ‘the precision of pain and the blurriness of joy’ [from “Open Closed Open”]. It’s true that there is a more thorough and more individual preoccupation with pain, but Amichai wrote, ‘I want to describe with a sharp pain’s precision / happiness and blurry joy,’ but there’s no need for that. It’s correct to look at negative emotions and positive emotions in different ways.”

The newly identified bias has adaptive value, but in certain cases it can also exact a price. For her part, researcher Genzer says that when trying to assess the emotions of a crowd of people, an extreme take can be problematic.

“It could be relevant, for example, in interactions between demonstrators and the police,” she says. “Sometimes there’s a moment at a demonstration when things heat up. And if the police think people are feeling something very negative, they may respond more aggressively to protect themselves and maintain public order – and that response in itself could escalate the situation.”

The bias could induce police officers to overestimate the level of danger they face, making them more likely to respond with excessive violence, which at times may be lethal – as may have been the case recently in the Bedouin town of Tarabin in Israel, or with ICE agents in Minnesota.

But one needn’t be a police officer in a volatile situation for the bias phenomenon to have negative effects. It’s enough to log onto social media, says Perry: “These platforms exploit our perceptual tendencies, such as the tendency to be more sensitive to negative information. Intensifying negative emotions is important for our survival in the world and even for empathy. But if we are predisposed to interpret others’ anger or hatred as stronger than they are, that can inflate negative perceptions of the Other. Social media exploits this mainly to keep us enthralled to them, while intensifying hatred and polarization.”

A 2023 study showed that social media in fact foster moral anger toward opposing political groups, beyond what reality warrants. “When we are captive to social media, we constantly think that dramatic and important things are happening, and that the other side is monstrous,” Perry says. “It’s good to be aware of the cognitive biases that contribute to this and sometimes distort the picture.”

In one interesting study conducted by the researchers, the participants were asked to assess how precise they think they are when it comes to understanding the intensity of others’ emotions, and, on the other hand, how precise others are in understanding the intensity of theirs. Most believed they read others well, while also believing that the others underestimated the intensity of their emotions. In the study, both beliefs turned out to be wrong.

In other words, we’re convinced that we understand others better than we actually do – and at the same time believe others belittle and diminish how difficult and painful things are for us. We’re wrong on both counts, but there’s a measure of consolation in both of these mistakes.