Photo: Feifei Cui-Paoluzzo/Getty Images

There is no sign of forced entry, though this is not something I generally scan for upon entering my apartment. But then I spot several of the ceramic drawers where I keep my jewelry, smashed on the bedroom floor. My first thought is: Earthquake? The cat has aged out of mayhem. Then I notice the rest of the drawers, turned over on the bed, and follow the trail to the open window. Most traumatic events present their size and shape fairly quickly. But some unfurl slowly, like a fist loosening its grip. When I call 911, my voice is urgent but searching. It’s the voice of someone who has run onto a train as the doors are shutting. Is this the express? Have I gotten on the express? It has never before occurred to me that 911 operators must hear an eerie amount of calm, of people seeking confirmation that they should be calling at all. The operator is in the midst of sharing a joke with her colleague when she picks up. She can’t quite pull it together in time. She says: “Nine-ha-ha-one-one, what’s your emergency?”

My friend Russell, who is dead now, enters this story before it begins. In a way, the thief is stealing from him, too. He was here first. The smashed ceramic drawers belong to a 1920s Dutch spice cabinet we bought together, along the grassy aisles of a flea market in Connecticut. This was fifteen years ago, back when I still worked in book publishing, back when Russell was still my boss, a moniker I kept using long after he stopped being allowed to tell me what to do. He wasn’t so fond of it when it applied. You know, he’d say, wounded, I introduce you to people as my friend. The fact that one of us could fire the other was immaterial. Our job titles, Executive Director of Publicity and Associate Director of Publicity, were meaningless strings of code.

The price of weekend visits to the house he shared with his partner was a 6:00 a.m. wakeup call to drive to the edge of a field and drink instant coffee from foam cups. His partner and I would groggily plod along as Russell zipped between blankets pinned down by cheap trinkets: cracked colanders, down-on-their-luck bunnies, cloudy prohibition bottles, pillows crocheted with “If you lived here, you’d be home by now.”

CHAPTERS

Adapted from Grief Is For People, by Sloane Crosley, which will be published by MCDxFSG on February 27.

A flea market is the perfect intersection of frugality and taste, and no one knew that better than Russell. No bazaar has seen a haggler like him — the impish smile of a child, the timeless charm of a movie star, the competitive edge of a Spartan. See that open face, like a doll’s, those gray-blue eyes, that thatch of salt-and-pepper hair, seemingly scalped from the roof of an English country house. It feels ludicrous to go on here, to launch into more description of this person I loved so much. A rare instance in which less information would make life easier. The narrowing of traits is a necessary betrayal of the dead, but one must tread carefully in these situations. Once, I was asked to blurb the memoir of a woman whose mother had died, but the more the book told me to think of her as the best of all mothers, the less I could follow instructions. I felt for the author, for the fact that this precious relationship was in the hands of someone unmoved by the details. But this is the price of writing not “I miss this person,” but “Miss this person as I do.” It’s too much laundering of empathy.

So, for now, in place of further description of Russell, I will ask only that you turn your attention to the time Martha Stewart Living offered to photograph his collection of mid-century earthenware water jugs. He refused. He feared he’d never know the joy of fleecing an unsuspecting vendor again.

“Just look at what they did to milk glass.”

Russell spotted the spice cabinet first. He dragged me by my sleeve to come see it, suggesting I could store jewelry inside. But in a land of five-dollar items, the cabinet cost more than a hundred dollars. I was embarrassed that I couldn’t get the seller to budge, so I bought some Girl Scout patches instead, featuring girls doing wholesome things. Like splitting logs. Russell insisted that if the cabinet was still there on our way out, I had to get it. He would drive it into the city himself.

“Told you,” he said, helping the seller wrap it up. “It was waiting for you.”

This is not your typical spice cabinet. It’s a massive item, three feet wide with a solid wooden frame into which slide fourteen white drawers, painted with green trim. It was manufactured in Holland, so the drawers are labeled in Dutch. Small ones are for pepper and saffraan, large ones are for suiker and thee. In the center is a ceramic door with a pewter knob. The door is labeled eieren. I’d say I don’t know on what planet eggs qualify as a spice, but I do know: The Netherlands. Behind the egg door are two thin wooden shelves with six holes each. They are ideal for dangling necklaces.

When the thief opens the egg door, he grabs the shelves as one might grab a bowling ball. Or as if one were an unusually aggressive beekeeper. He yanks them so roughly from their tracks, a gold chain gets caught and snaps in two.

While I wait for the police to come, I call Russell to confess what happened. He is my favorite person, the one who somehow sees me both as I want to be seen and as I actually am, the one whose belief in me over the years has been the most earned (he is not my parent), the most pure (he is not my boyfriend), and the most forgiving (he is my friend). There are, of course, days when he is not my favorite person, days when I would pay him to be less like himself. But my instinct to tell him everything and immediately, to empty my pockets of stories for him, has always been strong. It’s an odd sensation, to be an adult and look up to another adult. Not just to hold him in high regard, but to adopt his tastes and feel a sense of flattery when he adopts yours. The reason I was hesitant to demonstrate my poor haggling skills in front of Russell was because I wanted there to be no division between us. I wanted us to be the same, always.

Calling him really does feel like a confession, like I should have protected what I had while I still had it. It’s harder to tell Russell about the burglary than it will be to tell my own mother. She will be distracted by the matter of my personal safety. But Russell understands objects as avatars, more loyal than most, more tolerable than any. Which is why his reaction surprises me.

He is unmoored by the missing egg shelves. He dwells on their removal, as if this action is from the wrong heist movie. When I remind him of the actual jewelry that was taken — of the chain that snapped in two, of the rings he’s mindlessly turned over in his palm during talks on his porch — he steers the conversation back to the shelves. It’s just so unnecessary. Their absence from the cabinet has not added insult to injury; their absence is the injury. It will be a long time before I realize this is because Russell cannot stomach the sadness of the larger violation. He cannot stomach sadness period.

Two cops arrive. These are the responding officers. I lean on my doorframe as they clonk up the stairs, asking me how I am. I tell them “not awesome” and invite them in with a sweep of my arm.

“All right,” says the first cop, “give us the tour.” I walk them into the bedroom, where, as a group, we come to the conclusion that there’s a window in here. Then we file back into the main room, where the second cop informs me that my laptop is on the table. Three more cops show up, including one with a fingerprint kit. She has an air of competence about her. When she requests permission to dust, I wonder under what circumstances I would not want that.

“It makes a mess,” she explains. “You seem like a neat person.”

Normally, I would accept this as a compliment but I have already begun searching for clues as to how I could have brought this on. I have already begun wondering how much the external assessment of me as a person in the world, one who has enough material goods to require a cabinet, might have factored into this crime. This notion, that this is not a crime of convenience but one of calculation, is dangerous. I can sense it licking its lips in the corner. I get a lot of packages. That the packages contain books or galleys of books is not something I can explain to a criminal mastermind retroactively. I live in the West Village, in a mediocre building surrounded by extravagant fortresses. I can’t pay rent in this neighborhood and have nothing, though I can have nothing because I pay rent here. It’s a conundrum. Though perhaps no factor is so outlandish as the fact that, four years ago, I published a novel about stolen jewelry.

Our hero breaks into a French château to steal a necklace. He does this by scaling a wall and climbing through a bedroom window.

Did the novel do this? Rather, are there enough copies of the novel in circulation to do this? This line of concern is born from an unholy mixture of ego and paranoia. I wouldn’t entertain it were it not for one minor detail: forty-one pieces of my jewelry are missing. Amid the otherwise unremarkable loot are my grandmother’s amber amulet, the size of an apricot, as well as her green dome cocktail ring with tiers of tourmaline (think kryptonite, think dish soap).

As the cops ask me questions, staticky voices coming from their hips, my thoughts enter the seventh circle of sexism. Clearly this happened because I am a woman, trapped in a perfect storm of profession and age. I hail from a generation that beefed up résumés and deployed adverbs. We had to make ourselves appealing before the dawn of social media, when there was no daily pastiche of the self and therefore less space for self-deprecation. If you got anyone’s attention, you combed your hair and put your pants on. You made it count. As adults, women such as myself are caught in the messaging middle, after those who dressed up for planes, before those who dressed down for dates. Perhaps I have not done such a bang-up job as I thought, straddling the line between the Show-Off generation and the Whatever one.

Still, the idea that I have been punished for the dubiously impactful enterprise that is book promotion makes me want to punch a hole through the wall. I think of the older book critic who once crossed a party to chastise me for posting photos of myself on Instagram. Self-appointed custodian of that platform’s purity, the book critic decided: “Pictures should be of what you see, not of what the world sees when it sees you.”

“Do you have any enemies?” asks one of the cops, corralling my attention.

“Sorry, what?”

“Enemies.”

“Nemeses?”

“No, enemies.”

“Ah.”

The forensics cop is in my bedroom, unpacking her kit, adding objects to the room. Her job is so different from the thief’s. I make my way over to her and share my book promotion theory. When the novel came out, I explain, I wrote an article for a fashion magazine about the relationship between jewelry and sentimentality. She nods. She is feather-dusting a pile of paperbacks.

“There were photographs,” I say, as if she has spontaneously forgotten what we’re talking about, “in the magazine.”

“Of this apartment?” “No, of an old one.”

“Maybe the thief reads that magazine.”

I scoff, dismissing my own theory upon hearing it echoed back to me.

“Well, certainly not back issues.”

She snorts. I snort. We’re having fun, aren’t we? Considering?

At long last, a muscular detective arrives, squeezing past his colleagues. He’s wearing a purple tie and a gray suit that pulls at the armpits. He attempts to jog my short-term memory: Have I had anyone working in my apartment? A handyman? A housekeeper? I shake my head. A houseguest? A party? The only recent visitor is the man I broke up with one week prior.

Pencils down. Here is the whiff of an inside job, of less paperwork. I now must inform the room that this man didn’t exactly fight for our relationship. He wouldn’t recognize a piece of my jewelry if he swallowed it. Furthermore, he’s a creative director who paints on the weekends, and not like Francis Bacon. He’s not in touch with a criminal element. Still, I amuse myself, imagining what would happen if I let the police think this person was heartbroken enough for retaliation. I picture them searching his house, finding the axe he keeps nailed to a wall, not understanding this is a weapon only insofar as hipster affectation is a weapon.

“Maybe he cared more than you thought,” suggests one of the cops.

“No, he cared exactly as much as I thought.”

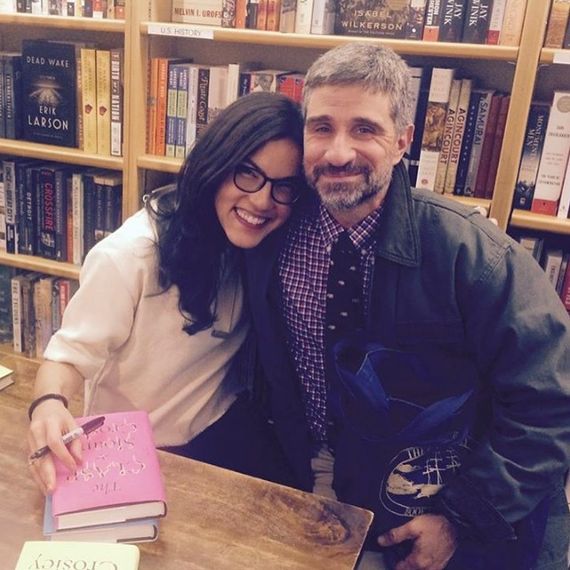

The author and Russell at her book signing in 2015.

Photo: Sloane Crosley

I’d been working for Russell for five years, in the publicity department at Vintage Books, the paperback arm of the fabled Knopf, when I stumbled upon my own résumé in the back of a filing cabinet. He must’ve been seeing a lot of candidates for my job, because he’d scribbled in the margins: Long brown hair. Square ring. I felt both chuffed and threatened by the other résumés pressed against mine — was there a world in which he thought we might not work out? On my pointer finger I wore the same ring, a square of tiger’s eye framed in silver, that he complimented the day he interviewed me.

Before I met Russell, I’d been employed by a more commercial publishing house, where my fellow assistants were in book publicity because they got lost on their way to corporate publicity or because they got lost on their way to academia. During my time there, one got promoted, one got fired, one left for graduate school, and two went to do PR for actual oil companies. But we were all victims of the same gnarly paper cuts from the same glossy author photos. We filled out the same overtime forms under the same recessed lighting and drank the same bomb-shelter coffee from the same mugs. And we were friends. Which is why, even after Russell offered me the job at Vintage, I was hesitant to jump ship. What if I didn’t like these new people as much? I asked to come in for a second interview.

It takes a special brand of brat to do what I did. I was twenty-five and proficient in nothing. But Russell allowed me to return to his office, where I unleashed a barrage of questions, all of which he gamely answered. When I was through, he exhaled in a way that seemed like a prelude to a dismissal. Plenty of people would take this job without even knowing to whom they’d be reporting. I was not yet familiar with the trajectory of Russell’s career, but I could sense the scope of it just by sitting across from him. His rolodex was open to the “C” tab. Caro, Robert. I later learned that, with the exception of a stint at Oxford University Press (“my walkabout,” as he called it), he had been with the company since 1990.

Russell put his elbows on his desk, leaned forward, and, with the greatest restraint he could muster, asked me what the hell I thought I was doing.

“Sorry?”

“Seriously,” he said, “what are you doing? It’s like you’ve been admitted to Harvard but first you need a tour of the bathrooms.”

At the turn of the century, Knopf was the most sought-after publishing house in America, both to be published by and to work for. The number of houses from which a “big” book could spring felt limited, and here, under one venerated roof, was the marketing budget of a small country, the first printings in the six-figures, and the brains of several dozen Nobel Prize winners. When a writer signed a book deal with Knopf, it was like a minor knighting. When a prestigious author turned out to already be published there, it was: Of course. Vintage was the paperback arm of it all, a dedicated department where those books lived on in perpetuity. It was an archive befitting the dead and a garden befitting the living. Home of classics, home of second chances. And Russell ran it. He had drunk the Kool-Aid. He had also mixed the Kool-Aid.

He instructed me to go over to his shelves, close my eyes, and pick a book. I was to go home that night, read it, and if I didn’t see any value in it, I didn’t have to work for him. His tone was casual but I could hear the worry behind it. He was twelve years older, thirty-seven, the age at which you start realizing that you only get so many loves of your life. But I was too young to start mourning connections the moment I made them.

I chose Heartburn by Nora Ephron.

Over the next decade, Russell delighted in telling people I was “working as a waitress in a cocktail bar” when he hired me. He had issued a course correction that would be imperceptible to the naked eye — I stopped commuting to one publishing house and started commuting to another, even the coffee was the same — but he knew better. Find one of us, pull the string, you’d find the other. Ours was the kind of partnership that felt transferable. Give us a designer’s discount and we will decorate your house. Give us some forceps and we will deliver your baby. Give us adjoining desks and we will crack your case. We moved fluidly among the roles of parent, child, sibling, and subordinate, swapping positions as they do in experimental theater.

The first time I published a piece of my own writing, an essay in The Village Voice, I thought I might have to avoid mentioning it at work. Or at least put its existence down as a fluke. The essay must have tripped and fallen into an editor’s in-box. Media was far more siloed then and one’s side ambitions did not make one more employable.

Russell papered the hallway with copies of the essay. He slid a few underneath occupied bathroom stalls.

This is someone who played tricks with equal enthusiasm. A puckish breeze blowing through some pretty self-serious trees, he served as office mascot. He’d rearrange the objects on people’s desks to see if they noticed or leave joke presents in our mailboxes. He’d cut out advertisements for medical creams and vacation packages to Siberia and tape them to our monitors. He set up a fake email account from my cat, from which I’d receive missives like “Mommy, how come you didn’t come home last night?” or “Mommy, how come you’re wearing the same outfit two days in a row?”

One afternoon, after we’d had lunch with an author I admired, I came back to my desk to find an email from Russell: See below. Let’s discuss. I scrolled down:

Dear Russell: What a pleasure it was to meet with you and Sloane today. Please don’t say anything, but she seems a bit young to be handling my publicity campaign. Is there a way you can oversee her more closely?

I felt a hollowness expand in my chest as I tried to take in the lines. Russell appeared in my doorframe.

“How should I respond?” he asked, unable to control the snickering.

I took a closer look at the email address, which was too obvious to be real. There was also a typo in the time stamp.

“You’re an asshole.”

It dawned on us both that I could forward the email to Human Resources. Russell dove for the delete key. I tried to block him, but he won, knocking over a full bottle of soda in the process. As we caught our breath, watching the soda drip over the cliff of my desk and onto a power strip, we realized the sent version of the email was still on his computer. He darted down the hall. I ran after him, lunging and grabbing his ankle, and we both went flying onto the unforgiving office carpeting. I scraped my elbow. The tiger’s-eye ring scratched his cheek.

“Children,” our boss greeted us, stepping over our prostrate bodies.

But like I said: There are no ankles left to be grabbed. It’s impossible to predict how much you’ll miss something when it’s gone, to game grief in advance. We fend off the worry that we’re taking our lives for granted by feeding ourselves the lie that we understand the value of their components. This belief is necessary for our choices, for the ordering of priorities. But it’s flimsy. You can play the game of identifying what you’d save in a fire all you want, but you will only ever be mostly right. I have a decent read on how much Russell means to me, having spent more hours of my adult life with this man than any other, but it does not occur to me that I am this attached to the jewelry until I start cataloging it for the police report.

A city of trinkets rises in my mind. Like any skyline, there are iconic sections, but there are also surprises that appear as I round each corner: a turquoise pin from a college friend, a beaded necklace from my niece, a pearl I dug out of the ocean with my own hands. I curse as I write their names.

“Fuck,” I say, “I guess I need better window locks.”

“Yeah,” says one of the cops, “that and a swear jar.”

Where this New York City police officer parked his turnip truck, I do not know, but I try to channel those Girl Scouts on their patches, those upstanding citizens. Alas, the patches are gone. They were in the motherfucking cabinet.

“You know what?” I say. “Welcome to New York. You get broken into and people curse here. Everybody gets to learn a lesson.”

I clap as I say it: Everybody. Gets. To. Learn. A. Lesson.

After I have my fingerprints taken, I escort everyone out the door. As I close it, I leave smudges on the brass doorknob. Fingerprints don’t disintegrate, and mine are all over this apartment, in various states of clarity. Perhaps the thief’s are here now, too. Somehow this is not as upsetting as the idea of my fingerprints outside the apartment, on the move, oily stowaways on stolen surfaces. Still, I’m glad to be alone. The robbery is gestating, maximizing and minimizing with each breath. I need silence so I can listen to it, so that I can understand its size. It’s emitting a steady moan that I do not yet understand is also about Russell. His cabinet. His taste. His bright idea. His satisfaction as he loaded it into the car. His prints mingled with mine.

I am up half the night cleaning fingerprint dust, which is, ironically, a lot like mopping up blood. You swirl carbon in circles until, four or five paper towel wads in, it agrees to come with you. Before bed, I scrub under my nails, but the pads of my feet will stay black for weeks. Weeks during which I will stand in front of the cabinet the way the cat stands in front of her automated feeder, as if trying to will its contents into the bowl. I touch my temple to the wooden frame. I am waiting for the things I love to come back to me, to tell me they were only joking.

Russell had zero facility for office politics. He was an excellent mentor so long as you didn’t expect anything resembling patience. He kept a quote, attributed to Louis XIV, pinned above his desk: “I have been almost obligated to wait.” This sort of blunt managerial style was not only tolerated but protected in book editors, who spent years crafting interpersonal gauntlets, doling out eye contact like a finite resource. Not so for publicists. We were hired to interact, to nudge, to smooth out the edges of any conversation. Shortly after I left Vintage to write full-time, I had an idea for a TV pilot, a comedy that would take place in the Human Resources department of a publishing house. Because I’d worked in the building and knew its personalities, the HR director agreed to share some “generally colorful” stories. No names, he emphasized in advance, and no guesses at names. Though he did ask me to produce one of my own: To whom had I reported again?

“Oh, well,” he said, “you could do a whole spinoff about that one.”

In his own defense, Russell loved to tell a self-styled fable from before my time, about the woman who came to him for an informational interview. She was organized and well-read and couldn’t understand why no one would hire her. Russell leaped at the chance to explain.

“First of all,” he said, “you asked me where my office was and it’s in the signature of my email. So you just told me you’d make more work for me. Second of all, you’re not fun. This is a seven-person department. I have to live with you.”

I could just see him scribbling in the margins of her résumé: Not fun.

Years later, when the woman became a successful newspaper editor, she wrote Russell a handwritten note, thanking him for this life-changing candor. He pinned it above his desk, too. Sometimes he’d wordlessly point, as if to say, “Talk to the note.”

“Uh-huh,” I’d say. “That’s one person.”

Russell was frank with those who reported to him because he expected them to be frank in return, to tell him when an author was unhappy, to edit the corny jokes out of his pitch letters, to chastise him for being late to a meeting. So many of us will accept adoration even if it’s not about us, even if it’s about the perception of us. Or some service we provide. We are happy to be cast in other people’s plays so long as we’re given a role. But Russell was adamant that he be adored for exactly who he was. Perhaps it had something to do with spending the first half of his life trying to blend into a world in which he could never fully be himself, where repression was the price of acceptance. Either way, Russell liked to say that after being loved, being adored is the best experience there is.

And once you established that you did, in fact, adore him, you had to maintain. It was like throwing a ball at a puppy. He’d send me a text and then appear in my office door, asking me if I’d read the text.

“Go away.”

“Are you annoyed at me?” “Yes.”

“Are you in a bad mood?” “I am now.”

But the second he sulked down the hall, I’d roll my chair after him, pleading for him to come back. Come back, come back. Please come back.

And then it was time for me to walk away.

There was a good reason editors and agents became writers themselves but publicists rarely did. In the age of the pitch call, it was an impossible situation. What started out as a nice problem to have (Local Girl Makes Good!) became a real problem to have. Every interview kicked off with the question of whether my authors were irritated with me for publishing a book of my own, a mostly laughable idea at Knopf. But occasionally it was true enough. Inside the office, I was being watched for signs of negligence. Outside the office, I was a novelty act. At one point, a books columnist told me he had room to cover either the book I’d written or the book I was calling to promote. I should pick.

The morning I quit, Russell came into my office, asking if I thought we should send an author to the Midwest for her book tour. I put my head between my knees.

“So that’s a no to Minneapolis?”

He was horrified. We’d made it through a decade of bomb scares and budget cuts, of layoffs and literary controversies, and I’d never lost it. What was wrong? Was it my parents? A man? Had I finally killed a man?

I took a deep breath and raised my eyes to meet his.

“Oh, God,” he said, slamming the door behind him.

As I hold the pieces of a ceramic drawer in place with one hand, waiting for the glue to dry, I answer email with the other. I am curious to find out how well I can function in the hours immediately following the burglary, knowing in advance what the answer will be: fine. No one is the first person to whom bad things have happened. Functionality is not the problem. The problem is that our capacity to handle something shocking in the short term can make things indistinguishable in the long term. You become numb when you swallow too much sadness at once. The reason it feels like no boundaries have been crossed is because the whole concept of boundaries has been obliterated. Maybe there is no such thing as an emergency. Maybe our days are not a mixture of upbeat and downbeat songs, but notes in the same maudlin song. You just haven’t hit the bridge yet.

Keep humming, you’ll get there.

People such as myself, who have mostly encountered anticipated trauma, “this is really going to hurt” trauma, are likely to find ourselves agape at the proximity of the ordinary to the extraordinary. The idea that misfortune arrives “out of the blue” means that the surrounding events become consequential in order to buttress the presence of the intruding event. You look back on the day of your car accident and remember how you broke a glass in the sink that morning. You never break glasses in the sink. What can be gleaned from this fact? To a person who does not expect trauma? Something cosmic. To a person who expects trauma? More or less nothing. Though, this state is not without its utility. As the poet Rainer Maria Rilke put it: “The person who has not at some point accepted with ultimate resolve and even rejoiced in the absolute horror of life will never take possession of the unspeakable powers vested in our existence.”

For years, my most frequently cited example of this metamorphosis from wide-eyed to world-weary was when my uncle left my aunt. She came home on their twenty-fifth anniversary to find that, in addition to packing up all his belongings, he’d relieved the paper towel roll from its dispenser. If you asked my aunt to tell this story in the months that followed, the paper towel would be the constant detail, always delivered in the same flabbergasted tone. As if to say: What is this doing in the story? Get it out of the story. But years later, she knows: It is the story. It’s all the same story.

Sometimes I worry I am projecting shared meaning onto completely unassociated events. It’s not such a nice world. Bad things happen. Sometimes they happen all at once. One day there will be only Russell and, on occasion, if I tell the story for long enough, a burglary that happened “around the same time.” But we are so far from the future. Right now, every time I try to separate these losses, to keep the first from contaminating the second, they come back together like magnets. Hideous sisters, they are keeping each other company in the dark. They are in conversation with each other. Sometimes I’m privy to the conversation, sometimes I’m not. They have their own language.

The day Russell died, he posted a picture of wildflowers on Instagram. “Rudbeckia running rampant along the north side of the barn,” he wrote. I suppose it’s a sign of our times that his last written words are in the form of a caption. Rudbeckia running rampant. What a pleasant series of sounds. It’s tempting to connect the photograph with what happened later that evening. That way the subsequent horror is not so out of the blue. That way the extraordinary has an on-ramp. It’s tempting to reach through the screen, place a palm against the barn wall, and whisper: Don’t. But it’s just a picture he took before he left the house.

Excerpted from Grief Is for People, by Sloane Crosley, which will be published by MCDxFSG in February 2024.

Source link