[ad_1]

In a previous post, we described the rapid growth of the stablecoin market over the past few years and then discussed the TerraUSD stablecoin run of May 2022. The TerraUSD run, however, is not the only episode of instability experienced by a stablecoin. Other noteworthy incidents include the June 2021 run on IRON and, more recently, the de-pegging of USD Coin’s secondary market price from $1.00 to $0.88 upon the failure of Silicon Valley Bank in March 2023. In this post, based on our recent staff report, we consider the following questions: Do stablecoin investors react to broad-based shocks in the crypto asset industry? Do the investors run from the entire stablecoin industry, or do they engage in a flight to safer stablecoins? We conclude with some high-level discussion points on potential regulations of stablecoins.

Reactions to Market-Wide Shocks

We study the impact of turmoil in the crypto-asset industry on stablecoin flows, focusing on large declines in the price of bitcoin, which, although caused by multiple factors, represent shocks to the overall crypto ecosystem. Specifically, our analysis uses data from January 2021 to March 2023 to estimate the impact of declines in the price of bitcoin on the net capital flows into stablecoins of different types and risk profiles.

As we did in our previous post, we divide stablecoin issuers into four broad categories: i) U.S.-based, asset-backed stablecoins (for example, USD Coin), which are backed by a portfolio of (mostly traditional) U.S.-dollar denominated assets, such as U.S. Treasury securities and commercial paper; ii) offshore, asset-backed stablecoins (for example, Tether), which are also backed by U.S.-dollar denominated assets but are based offshore; iii) crypto-backed stablecoins (for example, DAI), which are issued against other crypto-assets (typically with very volatile prices), such as Ether; and iv) algorithmic stablecoins (for example, TerraUSD), which are not backed by collateral and whose pegging mechanism relies on a supply-demand matching algorithm that exploits arbitrage between prices of different crypto tokens.

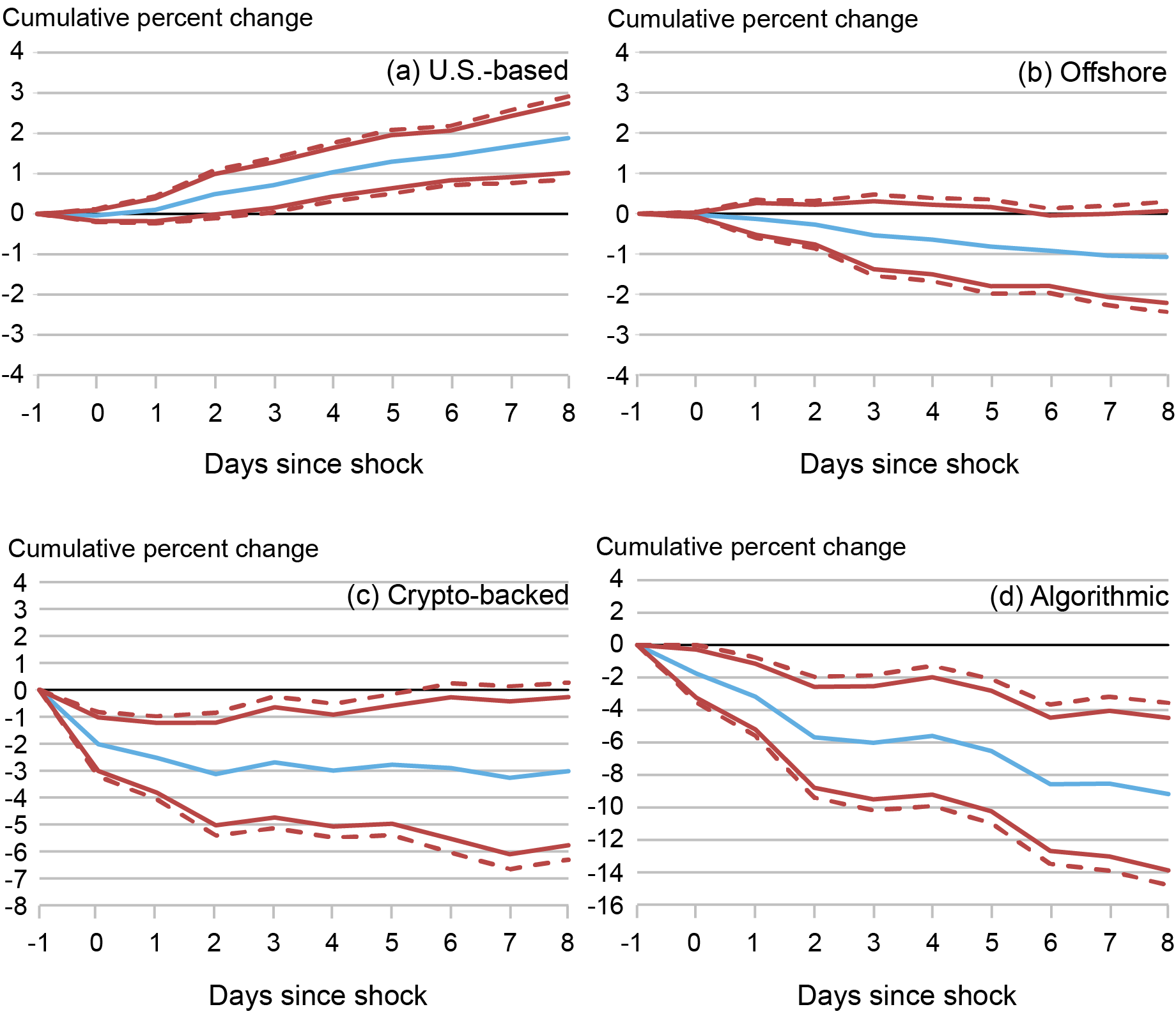

We then estimate the impulse response of cumulative net flows into stablecoins to shocks in bitcoin prices using local projections. The results are depicted in the chart below. Our estimates show a clear flight-to-safety pattern: after a negative bitcoin price shock, capital flows out of riskier stablecoins (offshore asset-backed, crypto-backed, and algorithmic; see panels (b)-(d)) and into less risky ones (U.S.-based asset-backed; see panel (a)). Our results imply that when the daily change in the price of bitcoin is in the bottom 5 percent of its historical distribution, risky stablecoins experience cumulative percentage outflows between about 1 and 9 percent, depending on stablecoin type, over the following eight days. In contrast, less risky stablecoins experience inflows of about 2 percent. Also, the outflow is largest for algorithmic stablecoins, consistent with the flight-to-safety hypothesis.

Impulse Response Functions for Various Types of Stablecoins to Bitcoin Price Shocks

These flight-to-safety flows are remarkably similar to those experienced by money market funds (MMFs) during periods of stress: In 2008 and 2020, investors redeemed heavily from prime MMFs, which hold riskier debt, and moved into government MMFs, which hold mostly U.S. Treasury and Agency debt and repurchase agreements collateralized by these instruments. These runs on MMFs amplified strains in short-term funding markets, which abated after extraordinary actions by the official sector. By the same logic, if stablecoins were to grow larger and more interconnected with the financial markets, runs on stablecoins could also become a source of financial instability and possibly require government intervention.

Discussion

Stablecoins are newer instruments than MMFs and more heterogeneous, both in terms of pricing and trading mechanisms; additionally, most jurisdictions lack a robust regulatory framework for stablecoins. Thus, questions on how to regulate them abound.

In a 2021 report, the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets, the FDIC, and OCC recommended that stablecoins, particularly those that are used for payments, be “subject to appropriate federal prudential oversight.” The report also highlighted the need to increase transparency in stablecoin arrangements, which could be accomplished, for example, by imposing a more uniform disclosure regimen for stablecoins. Of course, all regulatory options entail tradeoffs, and one would have to balance their costs with the benefits, chiefly those associated with improved investor protection and financial stability.

Summing Up

In addition to idiosyncratic run episodes experienced by algorithmic stablecoins in 2022, stablecoins also exhibit systematic flight-to-safety flows during periods of broad-based stress in the crypto asset market. That is, investors tend to run from stablecoins perceived as riskier into stablecoins perceived as less risky during such episodes. These dynamics are remarkably similar to those observed in MMFs during periods of stress.

Kenechukwu Anadu is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s Supervision, Regulation, and Credit Department.

Pablo Azar is a financial research economist in Money and Payments Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Marco Cipriani is the head of Money and Payments Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas M. Eisenbach is a financial research advisor in Money and Payments Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Catherine Huang served as a research analyst at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and is a Ph.D. candidate in Business Economics at Harvard University.

Mattia Landoni is a senior financial economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s Supervision, Regulation, and Credit Department.

Gabriele La Spada is a financial research advisor in Money and Payments Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Marco Macchiavelli is an assistant professor of finance at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Antoine Malfroy-Camine is a risk analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s Supervision, Regulation, and Credit Department.

J. Christina Wang is a senior economist and policy advisor in the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s Research Department.

How to cite this post:

Kenechukwu Anadu, Pablo D. Azar, Marco Cipriani, Thomas Eisenbach, Catherine Huang, Mattia Landoni, Gabriele La Spada, Marco Macchiavelli, Antoine Malfroy-Camine, and J. Christina Wang, “Stablecoins and Crypto Shocks,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, March 8, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/03/stablecoins-and-crypto-shocks/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

[ad_2]

Source link

JEWISH DIGITAL TIMES

JEWISH DIGITAL TIMES