[ad_1]

Governments increasingly use export controls to limit the spread of domestic cutting-edge technologies to other countries. The sectors that are currently involved in this geopolitical race include semiconductors, telecommunications, and artificial intelligence. Despite their growing adoption, little is known about the effect of export controls on supply chains and the productive sector at large. Do export controls induce a selective decoupling of the targeted goods and sectors? How do global customer-supplier relations react to export controls? What are their effects on the productive sector? In this post, which is based on a related staff report, we analyze the supply chain reconfiguration and associated financial and real effects following the imposition of export controls by the U.S. government.

The Growing Importance of U.S. Export Controls

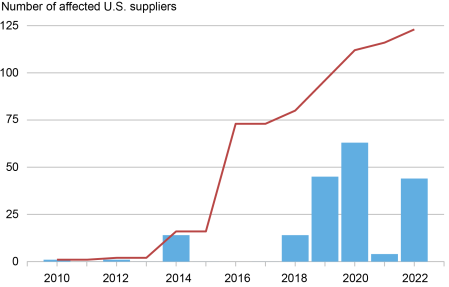

The Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) under the Department of Commerce forbids U.S. companies from exporting specific goods and services to a list of foreign targeted firms. We refer to such U.S. firms that supply goods to foreign firms targeted by export controls as affected U.S. suppliers. The targeted foreign firms primarily belong to the telecommunication, transportation, and electronic equipment sectors, while most affected U.S. suppliers operate in the electronics and industrial machinery equipment sectors. The chart below shows the growing number of affected U.S. suppliers in our sample.

Export Controls Affect an Increasing Number of U.S. Firms

Notes: The chart shows the number of affected U.S. suppliers over time as the Bureau of Industry and Security includes new foreign customers on the list of targeted foreign firms. The histogram shows the number of new affected U.S. suppliers in a specific year. The red line shows the cumulative number of affected U.S. suppliers over time.

To document the anatomy of export controls, we combine various data sources. We start by hand-collecting additions and deletions of foreign companies targeted by U.S. export controls from the Federal Register and the Code of Federal Regulations. Using FactSet Revere, we then obtain the identity of the suppliers and customers for each of these firms, as well as the dates when each supply chain relation starts and ends. Finally, we supplement this data with firm-level information from Compustat and Capital IQ, matched firm-bank loan-level data from the Federal Reserve’s Y-14Q, and stock price information from CRSP. For consistency, we focus on targeted firms located in China, as these represent most of the targets of export controls that can be matched with our supply chain data.

Broad-based Decoupling without Reshoring or “Friendshoring”

Export controls prompt a broad-based decoupling of U.S. suppliers linked to targeted foreign firms. Specifically, these U.S. suppliers are more likely to terminate relations with both customers targeted by the export controls and customers not targeted by export controls, but that are nevertheless located in the same country. This effect is sizable: export controls lead to an increase in terminations with any customer located in the country of the target foreign firm by 50 to 75 percent.

The affected U.S. suppliers also form fewer relationships with customers located in countries targeted by export controls by a staggering 60 to 68 percent. This decline points to a long-lasting decoupling, consistent with (i) a “wake-up call” as affected U.S. suppliers become more aware of geopolitical risk and the possibility of future controls and (ii) concerns that other customers located in the same country may re-export targeted goods to the directly targeted foreign firms, which would be a violation of export controls.

This broad-based decoupling by affected U.S. suppliers is not accompanied by friendshoring (with firms in allied countries) or reshoring (back home) in the three years following the imposition of export controls. U.S. suppliers affected by export controls do not form new supply chain relationships with domestic customers or customers located in countries not targeted by export controls, including countries geopolitically aligned with the U.S.

By contrast, the foreign firms targeted by U.S. export controls try to offset their effect by forming new relationships with local suppliers (foreign reshoring) and increasing purchases from their international suppliers unaffected by U.S. export controls.

Effect on U.S. Firms

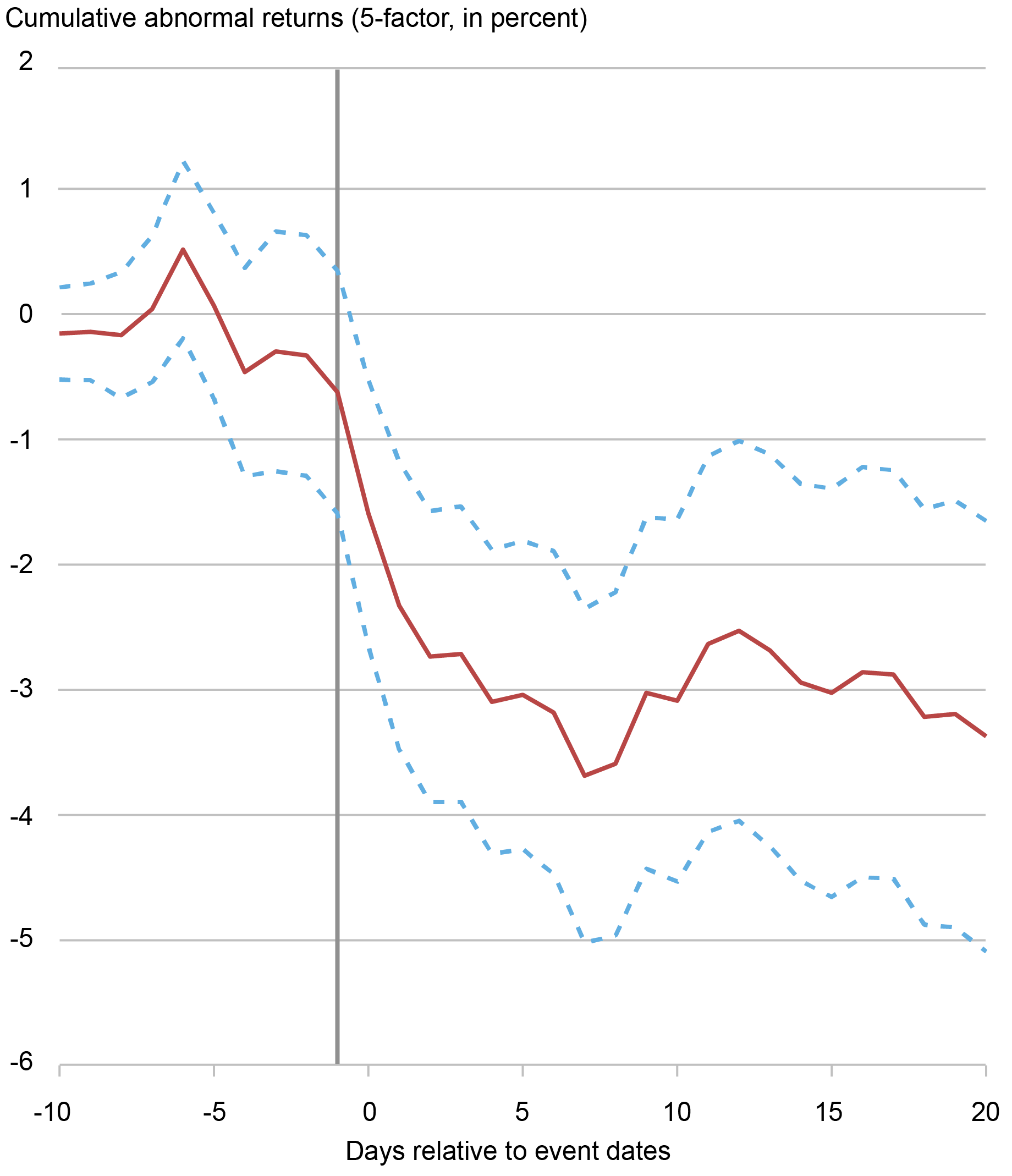

Consistent with the decoupling just discussed, U.S. suppliers are negatively affected by the export controls. The chart below documents the negative stock market reaction of these affected U.S. suppliers to news about the imposition of export controls. The Fama-French five-factor model around the announcement date documents sizable and persistent abnormal negative returns right after news about export controls hits the market. This -2.5 percent cumulative abnormal return in the twenty days after the imposition of export controls translates to an economically significant decrease in market capitalization of $130 billion in the group of affected U.S. suppliers.

Negative Reaction of U.S. Suppliers’ Stocks Is Shown following the Imposition of Export Controls

Notes: The chart shows the cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) of affected suppliers in a [-10, 20] day window around the announcement date of the inclusion of a target customer entity in the Bureau of Industry Security lists. The chart shows CARs using the Fama-French five-factor model (Fama and French 2015). On the vertical axis are the cumulative abnormal returns in percentages and on the horizontal axis the days relative to the announcement dates. The dashed vertical line represents the day before announcement date. The solid red line represents the average CARs and the dashed blue lines the 95-percent confidence intervals.

This drop in valuation is accompanied by a decline in revenues, profitability, bank credit, and employment among the affected U.S. suppliers. Capital expenditures remain stable, suggesting that export controls affect short-term profitability more than long-term investment opportunities.

Final Thoughts

Global supply chains are increasingly affected by governments’ desire to maintain control of strategic technologies. In this respect, export controls prevent selected goods from being exported to selected foreign firms, triggering a reconfiguration of domestic and global supply chains. At the same time, export controls impose collateral damage on the same firms whose technologies the government is trying to protect. As firms actively manage their network of suppliers and customers in response to export controls, these measures, as well as geopolitical considerations at large, are already shaping global trade.

Matteo Crosignani is a financial research advisor in Non-Bank Financial Institution Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Lina Han is an assistant professor of finance at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Marco Macchiavelli is an assistant professor of finance at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

André F. Silva is a principal economist in the Banking and Financial Analysis Section of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System’s Division of Monetary Affairs.

How to cite this post:

Matteo Crosignani, Lina Han, Marco Macchiavelli, and André F. Silva, “The Anatomy of Export Controls ,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, April 12, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/04/the-anatomy-of-export-controls/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

[ad_2]

Source link

JEWISH DIGITAL TIMES

JEWISH DIGITAL TIMES